Update on MIONJ and RANK-L Inhibitors

by DCDS

Written by: John W. Gannon, DDS (Dallas County Dental Society Member)

Bisphosphonates are widely known to induce osteonecrosis of the alveolar bone of the jaws. More recently, patients needing antiresorptive therapy for osteoporosis or bony malignancies are transitioning and beginning denosumab. Denosumab binds to RANK-L preventing activation of protein binding—mimicking endogenous osteoprogerin. Activation, migration, differentiation and fusion of hematopoietic cells of the osteoclastic lineage to promote the process of bone resorption are stalled. Osteoclast precursors in the bone marrow are reduced, further decreasing survival of osteoclasts in the blood and tissues, resulting in decreased bone resorption and increased bone density. Low doses, often bi-annual, are prescribed for post-menopausal women or patients at high risk for long bone fractures. High dose denosumab, administered monthly, is prescribed for the prevention of skeletal-related injuries in multiple myeloma patients, patients with solid tumor bone metastases and patients with hypercalcemia of malignancy which was refractory to bisphosphonates.

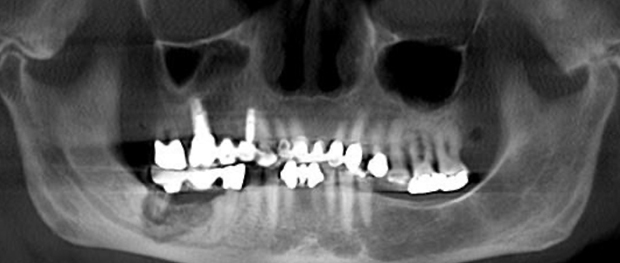

Denosumab has a much shorter half-life of 26 days compared to 11 years of bisphosphonates. The potency of denosumab often results in a more severe disease in patients than those taking bisphosphonates. This disease, drug induced osteonecrosis of the jaw (DIONJ), is defined as non-healing bone which has been exposed in the mandible or maxilla, that persists for greater than 8 weeks in the setting of a systemic drug such as bisphosphonates, denosumab, or anti-angiogenic drugs. DIONJ is staged 0-3: stage 0 is any radiographic evidence of osteolysis, stage 1 is exposed bone in 1 quadrant, stage 2 is exposed bone in 2 quadrants, and stage 3 is exposed bone in 3 or 4 quadrants, progression of osteolysis into the maxillary sinus and/or nasal cavity, or pathologic fracture. These stages do not vary regardless of pain, because exposed bone is not necessarily painful, but it becomes painful when the dead bone becomes infected. DIONJ is commonly initiated by extractions, traumatic occlusion, osseous periodontal surgery, trauma to tori or it may occur spontaneously. Alveolar bone and the lingual cortex of the mandible are commonly involved. The lingual cortex is more often seen than the buccal cortex due to the nature of the mandible flexing under masticatory forces. DIONJ risk factors include concurrent steroid and methotrexate use, diabetic patients, patients who smoke, patients with cancer and patients with severe periodontitis. However, these factors do not directly cause ONJ; but can accelerate the onset of ONJ, cause more severe ONJ, and cause a more extensive disease.

Preventive treatment in patients who are anticipating initiation of denosumab therapy should undergo a comprehensive dental examination. Non-restorable teeth should be extracted, restorable dentition should be treated appropriately, periodontitis should be treated including any osseous procedures. Patients who have already initiated denosumab therapy should avoid invasive procedures. If invasive procedures are unavoidable, a drug holiday is warranted prior to proceeding with treatment. Current protocol calls for a 3 month drug holiday prior to treatment and an additional 3 month holiday after.

DIONJ is not an oxygen-related problem similar to osteoradionecrosis, and thus hyperbaric oxygen and ozone treatments are not indicated therapies. DIONJ is a problem related to bone resorption and remodeling. In patients with exposed bone, it is important to try to avoid surgical treatment until a drug holiday is completed. Patients who are experiencing pain or infections can be treated initially with Pen VK or Doxycycline, and chlorhexidine mouth rinse. Metronidazole can also be added in patients with infections refractory to initial treatment. These are important steps to take in order to try to avoid surgical treatment when possible. Patients can remain on a prolonged course (years) of doxycycline 100mg daily or BID with chlorhexidine. In patients with symptomatic DIONJ that is refractory to antibiotic therapy, the next step is to consider surgical treatment, including debridement, alveolectomy and resection when necessary.

References

-

T Aghaloo, AI Felsenfeld, S Tetradis. “Osteonecrosis of the Jaw in a Patient on Denosumab.” J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2010; 68:959-963.

-

A Allegra, V Innao, N Pulvirenti, C Musolino. “Antiresorptive Agents and Anti-Angiogenesis Drugs in the Development of Osteonecrosis of the Jaw.” Tohoku J Exp Med 2019; 248: 27-29.

-

R Bujaldon-Rodriguez, G Gomez-Moreno, IO Leizaola-Cardesa, A Aguilar-Salvatierra. “Resolution of a case of denosumab-related osteonecrosis of the jaw after tooth extraction.” Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2019; 23:2314-2317.

-

N Dahiya, A Khadka, AK Sharma, N Singh, DBS Brashier. “Denosumab: A bone antiresorptive drug.” Med Jour Armed Forces India 2015; 71: 71-75.

-

E Dubois, R Rissmann, AF Cohen. “Denosumab.” Br Clin Pharmacol 2011; 71(6): 804-806.

-

C Egloff-Juras, A Gallois, J Salleron, V Massard, G Dolivet, J Guillet, B Phulpin. “Denosumab-related osteonecrosis of the jaw: A retrospective study.” J Oral Pathol Med 2018; 47:66-70.

-

S Hoefert, A Yuan, A Munz, M Grimm, A Elayouti, S Reinert. “Clinical course and therapeutic outcomes of operatively and non-operatively managed patients with denosumab-related osteonecrosis of the jaw (DRONJ).” Journal of Cranio-Maxillo-Facial Surgery 2017; 45: 570-578.

-

S Kuroshima, M Sasaki, T Sawase. “Medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw: A literature review.” Journal of Oral Biosciences 2019.